Views: 106

Quantitative rigor vs. ideological echo chambers in higher education

Frans Vandenbosch 方腾波 14.05.2025

STEM versus sociology

To render the discussion more transparent, it is first necessary to define the concept of sociology and to delineate the precise scope of the STEM disciplines. Which fields of higher education are classified as STEM (the so-called beta sciences or hard sciences), and which fall under sociology (commonly referred to as alpha sciences, soft sciences, or the humanities)?

According to Professor Wouter Duyck [1] ,[2] there exists a clear demarcation between STEM and sociology. The latter encompasses disciplines such as psychology, communication sciences, pedagogy, theology, journalism, political science, law, criminology, speech therapy, physical education and movement sciences, philosophy, language and literature, Eastern European languages, Eastern languages and cultures, African languages and cultures, ethics, art history, archaeology, anthropology, medicine, veterinary science, rehabilitation sciences and physiotherapy, pharmaceutical sciences, and applied linguistics.

Indeed, here in Europe, we conventionally classify the natural and medical sciences (医学科学- yīxué kēxué), veterinary science (兽医学 shòuyīxué), rehabilitation sciences and physiotherapy (康复科学与物理治疗 kāngfù kēxué yǔ wùlǐ zhìliáo), pharmaceutical sciences (药学 yàoxué), the humanities (人文学科 rénwén xuékē), and applied linguistics (应用语言学 yìngyòng yǔyánxué) under the umbrella of sociology or the alpha sciences.

By contrast, STEM clearly refers to Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics. This domain comprises numerous professions, including mechanical engineer, civil engineer, electrical engineer, chemist, bioengineer, data scientist, physicist, actuary, mathematician, materials scientist, geophysicist, and cryptographer, among others.

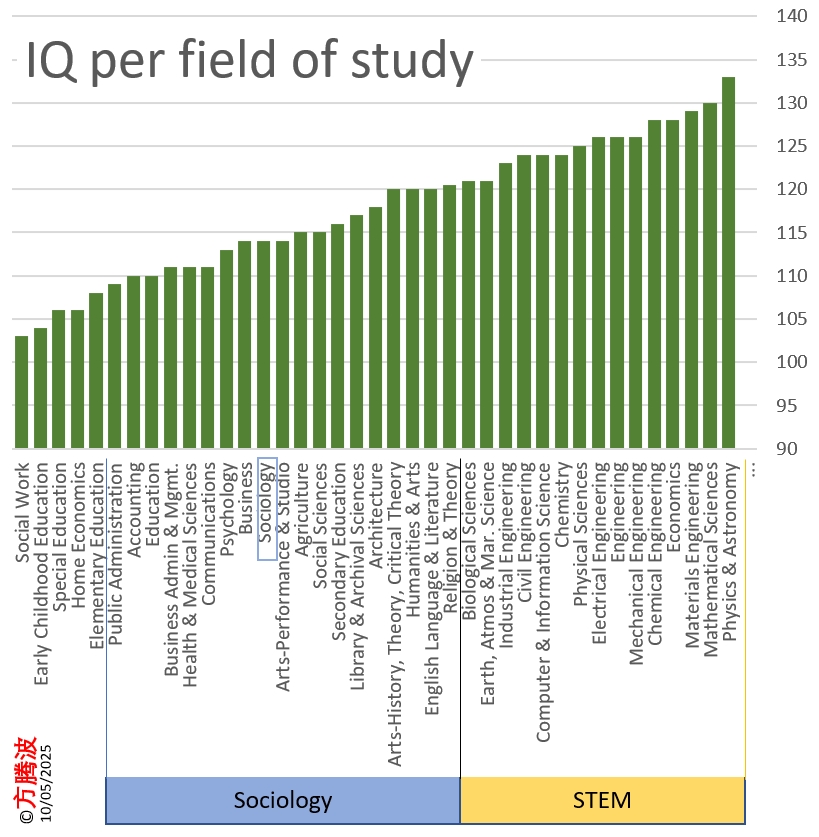

Not coincidentally, this same divide is also reflected in the Randal Olsen study [3] [4] concerning the IQ distribution among students of various academic disciplines.

Chinese versus western politicians

Given that nearly all Western politicians come from a background in sociology or similar ideological echo chambers, while their Chinese counterparts are overwhelmingly trained in STEM disciplines, the dysfunction of Western political systems needs no further explanation. Our leaders excel at spouting incoherent word salads, but when it comes to intellect, competence or dedication to the people, they are anything but cutting-edge.

Sociology in China

On top of that, in China, the discipline of sociology is approached with a markedly quantitative orientation, characterised by an emphasis on empirical data, statistical analysis, and methodical research techniques. Notably, at Nanjing University, students enrolled in criminology and legal studies programmes are required to acquire proficiency in AutoCAD, reflecting a broader interdisciplinary integration of technical competencies into the social sciences.

After several minor Gaokao reforms by the Chinese Ministry of Education, it was on 7 June 2023 in the afternoon that it became clear to the Gaokao candidates that the fun was over for the “Liberal Arts” students. The Mathematics exam was so hard for them that they had to step out and didn’t even participated in the science or language exams at the following day. On top of that, on 8 and 9 June 2023, some regions (Shanghai, Zhejiang, Guangdong …) had extra (optional) exams for elective subjects under the “3+1+2” reform. There, the troubled history students had to take their comprehensive exam, competing against physics-focused peers for fewer university slots.

In most western countries sociology education is close to indoctrination: analytical skills are not highly encouraged; sociology students are made clear to only rely on what’s regarded as “reliable sources”.

Which is outright dangerous, as it opens the door for intellectual brainwashing and government propaganda.

In numerous Western educational contexts, sociology instruction is adopting a prescriptive framework that prioritises adherence to established authoritative sources over the cultivation of independent analytical skills. This pedagogical approach often emphasises conformity to a narrowly defined set of “reliable” sources, potentially at the expense of fostering critical thinking and open-minded inquiry. Such an environment may inadvertently suppress intellectual autonomy and discourage students from engaging with diverse perspectives or challenging prevailing paradigms.

This concern aligns with philosophical analyses of indoctrination in education. For instance, Rebecca M. Taylor discusses the ethical implications of indoctrination, emphasising the importance of educators fostering environments that encourage critical examination rather than uncritical acceptance of information [5]. Similarly, discussions on the “hidden curriculum” highlight how implicit educational practices can perpetuate social control by promoting acceptance of specific values and norms without encouraging reflective consideration [6].

Moreover, the reliance on a limited set of sources and perspectives can create conditions conducive to ideological conformity, where alternative viewpoints are marginalised. This dynamic is reminiscent of concerns raised in critical discourse studies, where the suppression of diverse narratives can lead to a form of intellectual homogenisation [7].

To uphold the foundational academic principles of open inquiry and epistemic pluralism, it is imperative for educational institutions to critically assess their pedagogical approaches. Encouraging students to explore diverse perspectives helps them develop strong analytical and critical thinking skills. These skills are essential for fostering informed, independent individuals who can contribute meaningfully to societal discussions.

The forgotten servitude of sociology

The economy is traditionally divided into three interdependent sectors: the primary sector (extracting raw materials through agriculture, mining, and forestry), the secondary sector (transforming these materials into goods via manufacturing and construction), and the tertiary sector (providing services, from retail to education).

While all sectors are vital, the tertiary sector exists to serve the others, facilitating, distributing, or optimizing the value created by primary and secondary labour. Yet most sociologists, entrenched in the tertiary sector, have forgotten this hierarchy. They dismiss their role as servants to miners, farmers, and engineers, instead posturing as an intellectual elite. Their boast of being “highly educated” rings hollow when divorced from tangible output; unlike STEM fields, which solve concrete problems, sociology often produces self-referential discourse detached from the material realities sustaining society.

Worse, many sociologists reject the humility of service, instead adopting a priestly tone, lecturing the very producers they ought to assist. This dissonance mirrors the broader Western decline: a leadership class that prioritizes rhetoric over results, ideology over infrastructure, and self-aggrandizement over service. If sociology wishes to reclaim relevance, it must rediscover its place, not as a pulpit, but as a tool for those who build and feed the world.

Too many sociologists retreat into their moral high ground, treating ‘critical theory’ as mental comfort when confronted with their inability to explain, or even address, the real-world disruptions their ideas may exacerbate. Yet this is seldom intentional; it’s typically an unconscious byproduct of their ingrained academic habits.

Communication science

So-called communication science, particularly as practised in the spheres of Western politics and journalism, has evolved into a discipline uniquely unburdened by the constraints of empirical verification. Its primary output does not consist of testable hypotheses or verifiable models, but of syntactically flawless declarations that masterfully evade precision, accountability, or falsifiability. Statements are constructed with such semantic elasticity that they can mean anything (or, more usefully: nothing) depending on the needs of the moment. One might begrudgingly admire this rhetorical agility, where lexical sophistication is inversely proportional to informational clarity. For the masters in communication “science”, it is not the quality of the information provided to the public that counts, but the beauty of the word salad.

In its applied form, communication science functions less as a vehicle for transmitting truth than as a mechanism for manufacturing legitimacy. It equips politicians with the vocabulary of sincerity without the burden of substance, and journalists with the tools to shape public sentiment while preserving the appearance of neutrality. Concepts such as “narrative framing” and “agenda setting” are deployed not to interrogate power structures but to manage audience perception in ways that conveniently align with institutional interests.[8]

Were its practitioners to adopt methodologies more common to the natural sciences (such as reproducibility, falsifiability, or objective measurement) they might inadvertently discover inconsistencies in their own assumptions, or worse, contradict the ideological frameworks they are tasked with reinforcing. [9] Thus, it is perhaps no coincidence that western communication “science”, in its modern form, remains comfortably nestled within the “soft” academic disciplines: intellectually malleable, methodologically ambiguous, and ideologically aligned with the cultural apparatus it serves.

A call for intellectual renaissance in western academia

The stark dichotomy between STEM’s quantitative rigor and sociology’s ideological echo chambers exposes a crisis at the heart of Western higher education. While China integrates empirical discipline into its social sciences—producing leaders capable of solving real-world problems—the West clings to a system that rewards rhetorical gymnastics over substantive thought. Our universities have become factories of conformity, churning out politicians and “experts” skilled in crafting elegant word salads but devoid of analytical depth. We have a leadership class allergic to accountability, intoxicated by dogma, and utterly unequipped to address the complex challenges of our time.

If the West wishes to reclaim its intellectual vitality, it must dismantle the ideological monoculture masquerading as sociology. Let us demand curricula that prioritize critical inquiry over indoctrination, evidence over narrative, and competence over charisma. The alternative is irreversible decline, a fate we can no longer afford to ignore. The choice is clear: either embrace the rigor that built modern civilization, or perish in the echo chambers of our own making.

Thank you for reading! We’d love to hear your thoughts. Please share your comments here below and join the conversation with our community!

本文英文:理工硬科学与社会软科学的矛盾

Dit artikel in het Nederlands: De botsing tussen STEM en sociologie

Endnotes

[1] Prof. Wouter Duyck: De staat van het Vlaamse onderwijs. Pleidooi voor meer ambitie. Lecture on 10.12.2019

[2] Prof. Wouter Duyck: How interest fit relates to STEM study choice: Female students fit their choices better. Journal of Vocational Behaviour 129 (2021) 103614 Available online 24 July 2021 Elsevier Inc. https://users.ugent.be/~wduyck/articles/SchelfhoutWilleFonteyneRoelsDerousDeFruytDuyckInPress.pdf

[3] Randal S. Olson, “Average IQ of Students by College Major and Gender Ratio,” RandalOlson.com, 25 June 2014. Available: https://randalolson.com/2014/06/25/average-iq-of-students-by-college-major-and-gender-ratio. The data visualisation linked from Plotly (https://plotly.com/~etpinard/330/ ) is based on the same data and complements the original blog post. Olson sourced the figures from https://www.statisticsbrain.com/ and Educational Testing Services https://www.ets.org/

[4] Randal S. Olsen: Source: https://plotly.com/~etpinard/330/us-college-majors-average-iq-of-students-by-gender-ratio/#data Data derived from Randal Olsen https://randalolson.com/2014/06/25/average-iq-of-students-by-college-major-and-gender-ratio Source: StatisticsBrain.com and Educational Testing Services

[5] Rebecca M. Taylor, “Indoctrination and the Epistemic Value of Critical Thinking,” Journal of Philosophy of Education 51, no. 1 (2017): 38–58. https://academic.oup.com/jope/article-abstract/51/1/38/6821392

[6] Philip W. Jackson, Life in Classrooms (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1968).

See also: “Hidden Curriculum,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hidden_curriculum

[7] José Ángel García Landa, “Propaganda and/or Ideology in Critical Discourse Studies: Historical, Epistemological and Ontological Tensions,” Academia.edu, https://www.academia.edu/45550501

[8] Herman, Edward S., and Noam Chomsky. Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. New York: Pantheon Books, 1988.

[9] Carey, James W. “A Cultural Approach to Communication.” Communication, vol. 2, no. 1 (1975): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203876760

Frans, as usual, an article full of data with sound reasoning.

In this case, even if we accept that emotional intelligence is strongly correlated with the intellectual quotient, I claim that those qualities are not enough for good rulers.

You can be smart, capable with analyzing data and facts, and you can be skillful in interacting with others and I don’t say that having those attributes is useless for a ruler in sound decision making BUT there is something called loyalty or *esprit de corps* meaning sharing the same burning passion of relentlessly working in order to create or to re-create the glory of a nation, bringing together men of high talent around a leader embodying that collective aspiration, that’s the secret sauce.

So, intellect is not everything.

I don’t believe that high capacities in Maths, Sciences or Engineering, albeit desirable, are everything.

The man of vision (he can be of very high IQ but not necessarily), let’s say Xi Jinping, is surrounded by extremely competent technocrats, the very high IQ people : the 250 people of the CPC Central Committee, all the people of the State Council and all of the Commissions assisting him.

I know many people having high intellectual capacities but rather idiots for complex social situations and far to be capable of inspiring loyalty, which are after all at the center of any ruler endeavor.

I don’t deny the urgent need in the West of restoring a serious curriculum in Sciences & tech.

I also don’t deny your diagnosis that many of the people from Sociology have priestly attitudes but in a society with no more clear metaphysical framework, don’t you think it was a quasi natural occurrence ?

Going back to the rulers, it’s the political structure with elections desired by the oligarchs in the West having iteratively allowed clowns to be in power because it serves the oligarchical interests.

Are the Westerners ready and willing for a true revolution and pay the inevitable dear price ? Changing utterly the political framework based on emotional manipulations to something more meritocratic ?

Will the oligarchs allow such a change ?

To be or not to be, that is the question.

Quan

We’re not in disagreement. You’re right: it is not just high IQ, there’s much more required to be a good politician or statesman. The high IQ is a good basis; dedication to the people is at least as important.

“我将无我,不负人民”