Views: 252

Chinese researchers have found a “second answer”.

Frans Vandenbosch 方腾波 02.12.2023

This is a republishing of an article, written by Ms. Jia Yuxuan (Research Associate at Center for China and Globalization – CCG) on 24.11.2023 about Professor Qin Hui’s research in 2015, based on previous research in 2003.

Foreword

The two answers in brief:

1. More democracy. More and deeper, refined democracy, throughout all levels of society.

2. The subsidiarity principle with checks & balances, rigorously applied at all levels. The ‘cycle of separation of powers’, the lessons from China’s history.

How China Perfects the Art of Checks and Balances: Qin Hui on the Cyclicity of Chinese History Belief in inherent human evil leads to exploitation of self-interest, checks and balances, and autocracy oscillation and autonomy, a historical perspective that is still relevant today.

The combination of these two answers, the lessons learned from history and the study of the rise and fall of various civilizations and Chinese dynasties, guarantee the growth of Chinese prosperity for centuries to come.

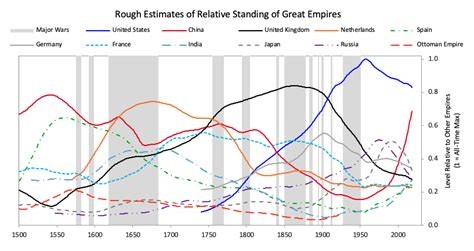

Ray Dalio, author of “Principles,” calculated that the lifespan of a civilization is usually between 300 and 500 years.

Only the Chinese civilization and culture can boast of having existed continuously for more than 5,000 years. For a brief description of the rise and fall of a number of Western and Eastern civilizations see a summary here:

https://finance.yahoo.com/news/ray-dalio-commentary-changing-world-202256827.html

Philippe Gouillou wrote an interesting study with many graphs and figures in “ The Lifespan of Civilisations ” (en Français)

On the rise and fall of Greek and Roman civilization, Cynthia Chung wrote for the Rising Tide Foundation: “How to Overcome Tyranny and Avoid Tragedy: A Lesson in Defeating Systems of Empire” (in English)

Dozens of books have been written about the causes of the fall of the (Western) Roman Empire. In 1984, Alexander Demandt listed 210 different theories about why Rome fell, and new theories have emerged since then. It is striking that these Western historians do not mention in any of these hypotheses the “two answers” (refined democracy and extensive subsidiarity) that have now been revealed by Chinese research.

China is not primarily a nation state, but a civilization state. For the Chinese, it’s about civilization. For Westerners it is nation. The most important political value in China is the integrity and unity of the civilization state.

With the newly acquired knowledge, combined with an almost perfect meritocracy, an administrative system based on scientific knowledge, integrity and sophisticated planning for the future, Chinese civilization is now on its way to eternity.

___________________________________-

The link to the source article: https://www.eastisread.com/p/how-china-takes-to-perfection-the

How China takes to perfection the art of checks and balances: Qin Hui on the cyclicality of Chinese history.

Jia Yuxuan 24.11.2023

Belief in inherent human evil leads to exploitation and self-interest.

Checks and balances, and oscillation between autocracy and autonomy, a historical perspective that remains pertinent today.

“Through painstaking efforts, the Party has found a second answer to the question of how to escape the historical cycle of rise and fall. The answer is self-reform” said President Xi Jinping in his report to the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC).

The first answer to the “historical cycle of rise and fall”, by the way, is democracy, proposed by Chairman Mao in 1945, who said, “Only when the people supervise the government, will the government dare not relax. Only when everyone takes responsibility, will there be no downfall of the government.”

The notion of the “historical cycle of rise and fall” echoes philosophical debates dating back to Hegel and presents an intriguing departure from the more linear progression typically associated with Marxist materialism. This cyclical interpretation posits that each successive stage of Chinese history mirrors its predecessor, seemingly void of novel creation.

Early do we see China advancing to the condition in which it is found at this day; for as the contrast between objective existence and subjective freedom of movement in it, is still wanting, every change is excluded, and the fixedness of a character which recurs perpetually, takes the place of what we should call the truly historical.

– G.W.F. Hegel, Vorlesungen über die Philosophie der Weltgeschichte. 1822

The following article is a dissection of this “historical cycle of rise and fall,” offering an in-depth yet succinct exploration of its political and administrative dimensions, while probing into the causes and mechanisms underpinning its perennial recurrence.

The author of the study “Historical cycle of rise and fall”, Qin Hui , is a retired as Professor of History, Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences, Tsinghua University, in 2017 and then served as a Visiting Professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. He is the author of the book Moving Away from the Imperial Regime (2015).

Originally a chapter in Prof. Qin’s 2003 book 传统十论 Ten Lectures on Chinese Traditions, this article is repeatedly reposted on webpages and in WeChat blogs, like the recent one by Zhoupeng 粥棚.

Recurring History, Cyclical Loops

连续的历史,循环的怪圈

After the collapse of the Ming Dynasty (1644), some intellectuals of the time, deeply affected by the circumstances, critiqued Legalist bureaucracy from a Confucian standpoint. In addition to quoting the grand Confucian principle of “天下为公” (All under Heaven belongs to the public), the critics also delved into governance methods. Huang Zongxi’s (1610-1695) insights were particularly noteworthy in this context:

The laws of later generations [as opposed to legendary times of wise and virtuous kings] deems the entire realm as within the pocket of the sovereign. No benefits are to be shared with the common people; all fortunes are amassed for the ruler alone. The appointment of one official is met with suspicion, leading to the appointment of another to oversee them. The implementation of one policy raises doubts about potential deception, necessitating the introduction of another policy as a safeguard.

Throughout the land, it is widely understood that the world’s bounty is concealed within the sovereign’s grasp, and that the sovereign, day and night, is plagued by concerns for their own private interests. Consequently, they are compelled to enact stringent decrees. Paradoxically, the more stringent the laws become, the greater the tumult that besets the world—this is what we term the paradoxical jurisprudence of an unjust legal system.

Han Fei (c. 280–233 BC) is the greatest Legalist in China who recognized that all people, commoners and elites alike, are inherently selfish and covetous. Hence, he advocated for the strict enforcement of laws and severe punishment for wrongdoing, without discrimination, to manipulate human desires and align them with the needs of the state.

As illustrated above, this practice of checks and balances, pitting individuals against one another and institutions against institutions, is deeply ingrained in the Chinese belief in the innate evil of human nature. It bears a resemblance to the Western concept of the balance of power, which originates from the recognition of the flaws in human nature. While the Confucian tradition emphasizes the inherent goodness of human nature, in practical legalism in China, people’s true perspective on human nature aligns more closely with that of Han Fei.

The ruler of men has two worries: if he employs only worthy men, then his ministers will use the appeal to worthiness as a means to intimidate him; on the other hand, if he promotes men in an arbitrary manner, then state affairs will be bungled and will never reach a successful conclusion. Hence, if the ruler shows a fondness for worth, his ministers will all strive to put a pleasing façade on their actions in order to satisfy his desires. In such a case, they will never show their true colours, and if they never show their true colours, then the ruler will have no way to distinguish the able from the worthless.

— Han Feizi (Writings of Master Han Fei), translated by Burton Watson

As a result, the inclination towards suspicion and the art of checks and balances, in Chinese culture, have grown to an extent that, if not unique, are at least exceptionally rare in the various civilizations of humanity. Those who are interested in this regard might do well to look beyond the classics of the “Four Books and Five Classics” [Confucianist canons] and explore traditional children’s “mengxue” (蒙学) works [a combination of nursery rhymes and textbooks] which often embody the genuine outlook on life and have a more widespread and palpable impact on society.

The Confucian classics teach that the purpose of reading and governance is to “cultivate oneself, regulate one’s family, govern one’s state correctly, and the whole kingdom is made tranquil and happy.” [from Daxue, also known as Great Learning, attributed to one of Confucius’ disciples, Zengzi] However, in Shen Tong Shi (神童诗, Poem for Prodigies) of Mengxue tradition, the plain truth is expressed with phrases like “A thousand pounds of grain [referring to the rich salaries of high-ranking officials] emerges from the book,” “A mansion of gold emerges from the book,” and “A jade-like bride emerges from the book.”

While the classics advocate the inherent goodness of human nature, the practical and honest wisdom in the Mengxue work Zeng Guang Xian Wen (增广贤文, Augmented Edition of Wise Words) tells us “To know a face is plain to see, yet knowing the heart is an elusive feat,” “Never let your guard decline,” “When meeting others, share just three in ten thoughts; keep your true self concealed, in the shadows caught.” “Cork your mouth and fortify your thoughts,” and offers proverbs such as “In mountains oft stand upright trees, the world ne’er sees one upright man,” “Relationships are as brittle as paper,” “None escapes the tongues of shame, still none resists a word of blame,” “Kind souls are oft exploited, like gentle steeds are ever heavy-weighted”, etc.

Mengxue works are intended for the general public, while the ruling “elite,” particularly the highest hierarchy represented by the Emperor, cannot be assumed to be any less astute than the common people. Their “art of ruling,” in fact, is grounded in an extreme view of human nature being inherently evil.

In medieval Europe, the governing structure was based on a system of layered “loyalty” between lords and vassals. Each lord appeared quite comfortable permitting their loyal vassals, who had sworn allegiance to them, to wield unchecked authority within their respective domains, resulting in a somewhat dumb system where “my lord’s lord is not my lord.”

This would be utter foolishness in the eyes of the Chinese emperors. They knew more than anyone that there are no truly upright people in the world, and no truly loyal ministers in the court.

- Household servants always engage in adultery, so they are castrated.

- Court officials always factionalize and pursue personal interests, so in addition to utilizing eunuchs as special agents for surveillance, political confidants are employed to decentralize their authority. This led to a system where the “Inner Court” overshadowed the “Outer Court.”

- Local officials always establish their own domains of influence, so central workgroups are frequently dispatched to disperse their powers, resulting in a system where inspectors often superseded permanent officials.

- Human nature is inherently unpredictable, so power has to be distributed among various government agencies. This will ultimately lead to fragmented governance, prompting the periodic need for concentrating authority, hence the cycle of separation and concentration of powers.

Many unique features in China’s traditional politics over the past several thousand years, such as recurring instances where eunuchs or the empress’s family dominated the court, are connected to this practice of checks and balances that stems from an extreme pessimistic view of human nature.

Primary Cycles of Checks and Balances

This “separation of powers” stemming from the Legalist-style doctrine of evil human nature grew increasingly pronounced throughout Chinese history.

The emperor dispersed not only the powers of the Counsellor-in-chief [the No.1 official under the emperor’s rule], but also the powers of the central government officials and local government officials. Regarding different categories of administrative duties, military, civilian, financial, and legal powers were separated among different departments. During the Ming Dynasty (1368 – 1644 AD), the judiciary authority was divided among the “Three Judicial Offices,” which included the Ministry of Justice, the Censorate, and the Court of Judicial Review. The military authority was split among the Ministry of War, the regional military commanders-in-chief, and non-permanent generals.

There were even layers upon layers of supervision and espionage: First, the Brocade Guards (锦衣卫, comprising of the emperor’s personal body guards) was established to spy on government officials; then the Eastern Depot (东厂, comprising of eunuchs) was created to monitor the Brocade Guards. Subsequently, the Western Depot (西厂, also comprising of eunuchs) was set up [to balance and disperse the powers of the Eastern Depot]. And finally, the Palace Depot (内行厂), also under eunuchs’ administration) was established, with supervising authority over the Brocade Guards, the Eastern Depot, and the Western Depot. Because the Emperor trusted no one and wanted to control everything, a fool proof system was never in place. Powers were continually divided and redistributed, giving rise to the unique historical phenomenon of the “cycle of separation of powers” in China’s history.

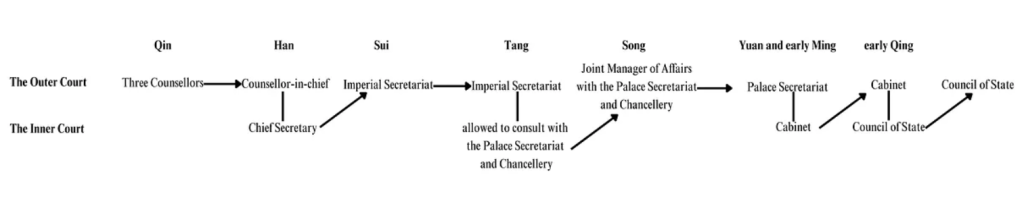

The cycle of the Inner Court and Outer Court

Throughout dynastic history, emperors always harboured suspicions that court officials were conspiring treacherous schemes and Counsellors-in-chief were plotting betrayal. Consequently, they opted to rely on political confidants and trusted advisors (the “Inner Court”) to channel power from the Outer court, sometimes even side-lining the Outer court.

However, as these once-favoured confidants gained influence and responsibilities, they evolved into a new “Outer Court,” once again arousing suspicions. So, the emperor would establish another group of confidants and advisors to undermine their influence.

For example, in the Han Dynasty (202 BC–9 AD), the Counsellor-in-chief held sway over all other officials and court affairs, so the emperor entrusted the Chief Secretary (尚书), who was originally responsible for document management to divide his power. This evolved into the Imperial Secretariat (尚书省) spanning from the Han Dynasty to the Sui Dynasty (581-618 AD), with the secretaries becoming the new de facto Counsellors-in-chief.

Consequently, during the Tang Dynasty (618–907 AD), emperors once again placed heavy reliance on close courtiers who were “allowed to consult with the Palace Secretariat and Chancellery” (同中书门下) and used them to marginalize the Imperial Secretariat. [The Palace Secretariat and Chancellery in the Tang dynasty were the deliberative and executive bodies of government, respectively.]

By the Song dynasty (960–1279 AD), Joint Manager of Affairs with the Palace Secretariat and Chancellery, (同中书门下平章事, abbreviated as同平章or平章) had evolved into new the Counsellor-in-chief and head of the Outer Court called the Palace Secretariat (中书省).

Therefore, in the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 AD), emperors assembled a group of “Grand Academicians” (大学士) close to them to form the “Cabinet” (内阁) to side-line the Palace Secretariat, eventually leading to the abolition of the position of Counsellor-in-chief (1380). However, in the later period of the Ming Dynasty, the Cabinet also gained significant power, and figures like Yan Song (严嵩, 1480-1567 AD) and Zhang Juzheng (张居正, 1525-1582 AD), who were once Grand Academicians, transformed from secretaries into effective Counsellor-in-chief that held real political sway.

As a result, the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911 AD) saw the emergence of secretariat teams like the Southern Study (南书房) and the Council of State (军机处), aimed at side-lining the Cabinet. Many historical accounts suggest that the establishment of the Council of State “ultimately” resolved the issue of contending powers between the emperor and the Counsellor-in-chief. However, wasn’t the initial setting of the Chief Secretary back in the reign of Emperor Wu of Han (141-87 BC) also considered the “ultimate” solution? Without the 1911 Revolution which overthrew the Qing Dynasty, one can imagine that the cycle of secretariats side-lining the Outer court would continue indefinitely. Even after the 1911 Revolution, didn’t we witness, over 60 years later, another secretariat team leading the “Cultural Revolution Group” (中央文革小组), side-lining the Politburo, and challenging the authority of the Counsellor-in-chief?

This cycle can be illustrated as follows:

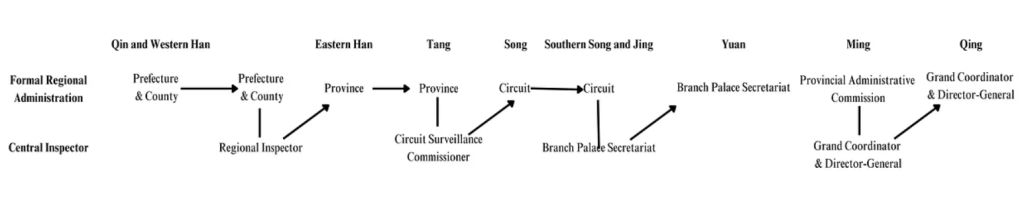

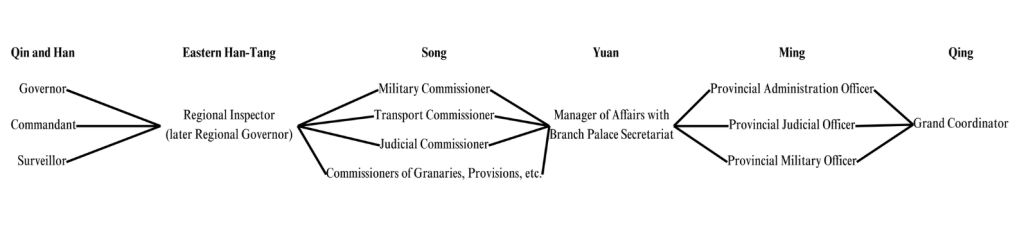

The cycle of central inspectors and local potentates

Throughout history, emperors have always suspected local officials of having hidden agendas. Consequently, they frequently dispatched central representatives to inspect these regions and endowed them with significant authority.

Over time, these central representatives shifted from merely intervening in local affairs to assuming a more dominant role in local governance. They progressed from dividing the authority of local rulers to side-lining them altogether. Temporary envoys became influential local power players, eventually evolving into a new generation of local rulers. Subsequently, the Emperor would dispatch new central representatives to scrutinize the same territories.

For instance, during the Qin Dynasty, prefectures (郡) and counties (县) constituted formal local government entities. However, the Emperor remained apprehensive, leading to the establishment of Regional Inspectors (刺史) during the Han Dynasty. Each one of the Regional Inspectors was tasked with overseeing one of the Thirteen Provinces (州), which were initially designated as areas for inspection responsibility. The Inspectors were primarily responsible for conducting inspection tours, as opposed to serving as permanent officials. Nevertheless, as the Han Dynasty neared its end, the authority of these Inspectors gradually expanded. They transitioned from being mere intermediaries to becoming influential figures in their own right, ultimately transforming from central representatives into new local officials. Consequently, the provinces evolved from being inspection areas to higher-level administrative regions beyond the prefectural level.

Consequently, the central government began to worry that the power of Regional Inspectors in each province had become too entrenched. During the Tang Dynasty, new positions known as “Circuit Surveillance Commissioners” (诸道按察使) were established to oversee various prefectures. During the Song Dynasty, changes in administrative divisions introduced circuits (路) as higher-level administrative units above the provinces. The officials in charge of these circuits (路官), such as Pacification Commissioners (安抚使), evolved from being mere inspectors to becoming top authorities in their respective regions.

This led to renewed suspicions from the imperial court, prompting the dispatch of representatives to the various circuits to “manage affairs with branch Palace Secretariats,” (行中书省事, abbreviated as 行省) effectively acting as central representatives with special assignments. At that time, these “Manager of Affairs with Branch Palace Secretariats” were still officials dispatched by the central government and part of the central Palace Secretariat. However, by the Yuan Dynasty, these branch secretariats had evolved into higher-level administrative regions above the circuits, and the “Managers of Affairs” (行省平章) became the new rulers of these regions. Consequently, new central representatives arrived once again, and this marked the emergence of the “Grand Coordinators” (巡抚) during the mid-Ming Dynasty.

The full title of the Grand Coordinator was “Vice (or Associate) Censor-in-Chief Coordinating the Censorate of ×× Province,” sometimes with the additional title of Vice Minister of War (兵部侍郎). So the Grand Coordinator was colloquially known as (部院), which indicated that they were officials dispatched by the central supervisory institution (the Censorate) or the central military institution (the Ministry of War). However, by the end of the Ming Dynasty, the role of the Grand Coordinators had shifted from temporary inspections to permanent positions, and their authority had increased significantly. Proper provincial officials, such as Provincial Administrative Commissioners (buzheng shi, 布政使) became nominal positions. After the Qing Dynasty’s conquest, the Grand Coordinators eventually became the top provincial officials, akin to regional governors.

This cycle can be illustrated as follows:

The cycle of separation and concentration of local authority

Also due to the Emperor’s suspicions of local rulers (诸侯), imperial courts across dynasties tend to separate various facets of local administrative powers. They allocated military, civil, financial, and judicial powers to different officials, ensuring that these powers remained distinct and parallel, each reporting to their respective higher authorities at the central level, all in an attempt to maintain checks and balances. However, such a system often proved highly inefficient. With multiple agencies involved in decision-making, governance became fragmented; officials would often shift blame onto one another or sink into inter-departmental disputes in times of crisis, sometimes resulting in complete paralysis of government functions.

As a result, it became necessary to appoint a higher-ranking official to oversee the various aspects of governance and concentrate authority. However, this also risked excessive concentration of power which undermined central authority. Thus the pendulum would swing back again toward separation.

During the Qin and Han Dynasties, for instance, the powers on the prefectural level were initially separated, with the Prefectural Administrator responsible for administration, the Prefectural Commandant overseeing military affairs, and the Prefectural Censor managing judicial matters and inspections. These three branches of government operated independently of each other.

From the Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 AD) to the Sui Dynasty, however, Provincial Inspectors began to wield significant authority, taking control over the military, civil, financial, as well as the judicial system, resembling local emperors in their own right. By the time the Song Dynasty established the circuit system, new offices such as the Military Commission (帅司), the Transport Commission (漕司), and the Judicial Commission (宪司), each under the leadership of a head official, were introduced on the circuitial level in order to divide the authority of provincial governors and military commanders. This was a typical system of local separation of powers.

During the Yuan Dynasty, with the emergence of provincial administration, local authority was once again concentrated. Managers of Affairs became the paramount leaders of their respective provinces, wielding significant power within their domains, and conflicts flared up among the provincial armies in the middle of the Yuan Dynasty. By the end of the Yuan Dynasty, this concentrated system of power had even led to the rise of provincial warlords who controlled their territories.

Recognizing these issues, the Ming Dynasty abolished the position of Managers of Affairs and established three offices within each province: the Provincial Administration Office (布政使司) under the jurisdiction of the Palace Secretariat, responsible for civil matters; the Provincial Judicial Office (按察使司), under the jurisdiction of the Censorate, responsible for judicial affairs; and the Provincial Military Office (都指挥使司), under the jurisdiction of the Commander-in-Chief’s Office, responsible for military affairs. These three offices operated independently of each other, eliminating the concentration of power. However, while this addressed the issue of warlordism, it led to bureaucratic disputes and inefficiencies. By the late Ming Dynasty, the widespread appointment of Grand Coordinators became necessary to unify the authority of these three offices. After the Qing Dynasty’s conquest, Grand Coordinators and concurrently established Director-Generals (总督) became powerful regional authorities. This pattern continued into the late Qing Dynasty and the early Republic of China, with military warlords exerting control in various regions.

This cycle can be illustrated as follows:

The cycle of peripheral power and grassroots autonomy

In addition, there are several similar cycles, such as the cycle of peripheral power and grassroots autonomy. Throughout Chinese history, governments have attached great importance to extending their top-down bureaucratic structures to every rural household, following the Legalist concept of “uniform registration of the population.” However, this approach had its downsides, leading to excessive control, administrative chaos, and high operational costs.

Consequently, adjustments were made, local autonomy at the grassroots level was introduced, and the government retracted one or two levels from the periphery of political power. Nevertheless, this shift often gave rise to local strongmen who wielded authority within villages and townships, challenging the control of the authoritarian regime. As a result, political power extended back to the periphery.

For instance, in the Qin Dynasty, the Legalist government not only prohibited the formation of clan settlements but also instituted intricate village and precinct organizations. They also introduced the “lüli shiwu” (闾里什五) system [which involved selecting leaders based on groupings of every five and ten households. These leaders were tasked with maintaining local security and had the responsibility to report any individuals with suspicious behaviour.] At that time, local “village officials” were often compensated for their roles and were chosen based on their strength and worthiness rather than their local reputation or moral standing. Some were even outsiders who held official titles granted by the state and carried out official tasks.

However, by the Eastern Han Dynasty, local clans had risen in prominence, and the village-based administrative system declined. Local elites became the influential “clan leaders” who operated independently of central authority.

Later, the imperial court of the Northern Wei Dynasty, in an effort to regain control at the grassroots level, abolished clan leaders and established a three-tier system of 5, 25, and 125 households. However, local community organizations gradually returned to greater autonomy during the Sui and Tang Dynasties. As a result, during the Northern Song Dynasty, Wang Anshi, then Counsellor-in-chief, implemented the baojia system (保甲法) [also known as the village defence law or security group law] which aimed at reorganizing rural communities.

This recurring cycle of peripheral power and grassroots autonomy persisted, with the Yuan Dynasty, Ming Dynasty, and the Republic of China (1912-1949) each reintroducing similar rural administration systems at various points in history.

Glorious Achievements and Great Destruction

Such political cycles, characterized by exploitation of self-interest to counteract self-interest, institutional checks and balances, the pendulum between autocracy and autonomy, perpetual suspicion of subordinates, and persisting cyclicality spanning thousands of years, is way beyond the tender theory of Confucius that “Good governance means that the prince is prince, and the minister is minister; the father is father, and the son is son.”

It should be noted that this intricately designed system of governance was indeed highly mature, even “modern” or profoundly “rational,” under traditional political conditions. While Western medieval relations between lords and vassals were still in a state of “loyalty” chaos, the Chinese had already taken the art of guarding against one another to near perfection.

The Western transition from aristocracy to civil service occurred much later than China’s shift from the rule of eminent families to bureaucratic rule. In certain aspects, Western systems were influenced by the Chinese Imperial Examination System (科举). Moreover, Western societies were unable to set aside their pride and did not adopt the practice of China, that is, deploying armies to closely monitor candidates one-on-one to prevent dishonest behaviour in their aspiration for “a thousand pounds of grain,” “a mansion of gold,” or “a jade-like bride.”

However, these two concepts of “human nature as inherently evil” and “checks and balances” are fundamentally distinct. The Legalist belief in “evil human nature” leads to extreme despotism—more despotic than aristocracy, whereas the modern Western interpretation of “evil human nature” leads to anti-despotism—more democratic than aristocracy. The former revolves around imperial authority, as articulated by Huang Zongxi, with the goal of safeguarding the world “within the pocket of the sovereign,” signifying the intention to confine the world’s control within the private domain of a single family and prevent interference from others. In contrast, the modern Western concept of “checks and balances” centres on individual rights, and the use of power against power is aimed at preventing tyrants from monopolizing the public sphere. The former upholds divine imperial authority, while the latter safeguards inherent human rights.

Therefore, it’s no surprise that the gap between these two theories of “evil human nature” and two systems of “balance of powers” is even wider than the gap between each of them and the ideas of human goodness and harmony (such as China’s Confucian ethics and medieval Europe’s feudal lord-vassal relationships). So, it’s not hard to grasp why, during the era of “criticizing Confucianism and promoting legalism” in the 1970s, when China steered away from Confucian principles of benevolence and righteousness and the traditional virtues of warmth, humility, respect, and frugality, it didn’t move closer to democracy and constitutionalism but rather drifted farther away.

From a practical perspective, though, this “rationalized” system has endured exceptionally, mainly due to these two reasons: On the positive side, it has shown remarkable resilience due to its strong focus on administrative security. Additionally, its highly intricate system of checks and balances, primarily designed for political safeguards, has also played a role in regulating governance and curbing officials from engaging in harmful actions towards the people. These two factors have allowed this system to persist for over two thousand years since the Qin dynasty without encountering any truly viable alternative, accumulating impressive achievements over an extended period of continuity.

However, on the flip side, the inherent, fundamental flaws within this system are insurmountable. Therefore, its continuity doesn’t result in long-lasting stability but is achieved through the various cycles mentioned earlier. In reality, these cycles represent the outbreak of accumulated problems and lead to significant disruptions, which are just as astonishing as China’s cultural accomplishments. Over more than two thousand years of history, this recurring drama has played out following a pattern encapsulated in an old Chinese adage, “division inevitably follows an extended period of unity, and unity inevitably returns after an extended period of division; chaos begets order, and order begets chaos.”