Views: 336

How Confucian culture first delayed and then accelerated China’s innovation.

Frans Vandenbosch 方腾波 04.07.2025

Smashing the European myth

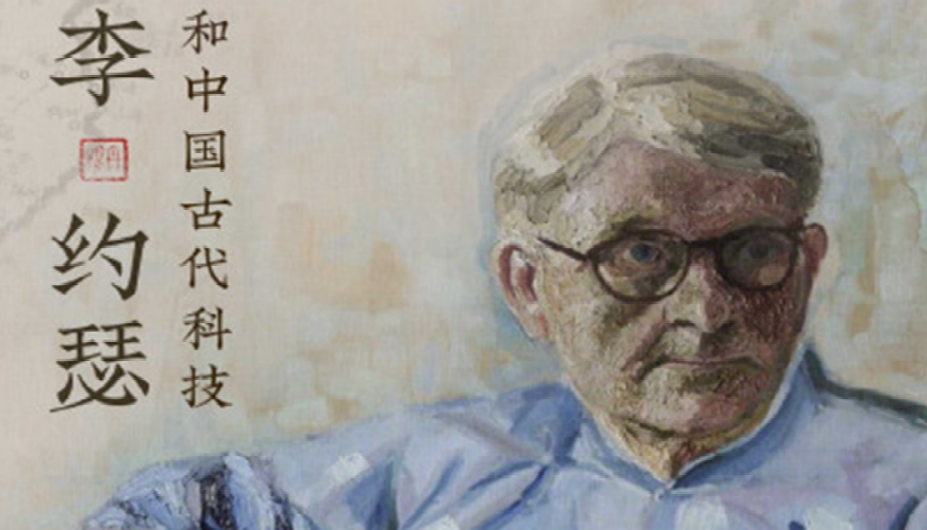

For centuries, Western narratives have portrayed science and technology as exclusively Western achievements, overlooking China’s profound contributions. Joseph Needham’s Science and Civilisation in China shattered this myth, revealing how China pioneered key innovations long before the West.

From mathematics and physics to dining culture and governance, China’s historical advancements challenge Eurocentric views of progress. This article explores these overlooked achievements, contrasting them with persistent Western biases and examining China’s modern scientific resurgence. By revisiting Needham’s work and contemporary developments, we uncover a civilization that never faded; it simply followed a different path.

Joseph Needham’s Science and Civilisation in China stands as one of the most monumental scholarly achievements of the 20th century, spanning 36 volumes that meticulously document China’s profound and often overlooked contributions to science and technology. When first published, it shocked the Western academic world by revealing that many so-called “Western” innovations (such as paper, printing, gunpowder, and the compass) were in fact developed centuries earlier in China. Needham’s work fundamentally challenged Eurocentric narratives of progress, proving that China was a global leader in science for much of its history. Despite the overwhelming evidence he presented, some sceptics and ideologues still refuse to accept the depth and significance of China’s early scientific achievements. To this day, Needham’s findings remain controversial among those who cling to outdated notions of Western superiority. His magnum opus remains not only a towering intellectual achievement but also a powerful corrective to historical amnesia.

China’s embarrassment of riches is an English idiom, applied by Joseph Needham to describe China’s overwhelming number of early scientific and technological achievements. The expression reflects Needham’s awe and the central puzzle of the “Needham Question”: why such a rich technological tradition did not lead to an early scientific revolution in China.

This historical whitewashing wasn’t accidental. It served a colonial narrative. But the deeper mystery isn’t what China invented, but why this didn’t lead to a Western-style scientific revolution in China.

The Confucian brake

The Needham Question explores why China, the home to ground-breaking inventions like paper and the compass, did not develop modern science before Europe, despite its early technological dominance. One key factor may lie in Confucian values, which emphasized harmony, humility, and respect for tradition, discouraging the bold questioning of nature that fuelled Europe’s Scientific Revolution. Unlike Europe’s competitive, individualistic thinkers, China’s scholars often focused on moral and administrative wisdom rather than disruptive scientific theories, aligning with a society that prized stability over radical innovation. Additionally, the imperial examination system reinforced classical Confucian texts over experimental science, steering intellectual energy toward state service rather than pure discovery. Yet, this doesn’t mean China “fell behind”. Its advancements were simply guided by a different philosophy, one that valued practical knowledge and societal order in ways Europe did not.

Boasting, American exceptionalism, virtue signalling: In traditional Chinese culture attitudes involving boastfulness are generally regarded with disapproval for they tend to undermine the virtue of humility (谦逊 qiānxùn) which plays a vital role in fostering harmonious interpersonal relations. Such conduct is perceived as contrary to the cultural emphasis on modesty and the preference for collective achievement over overt displays of personal success. Additionally, the notion of American exceptionalism which asserts inherent superiority is at odds with the Confucian ideal of self-reflection and the value placed on collective progress rather than national glorification. The practice of virtue signalling whereby individuals openly exhibit moral attitudes primarily to gain social approval is often viewed as inauthentic or hypocritical since it conflicts with the Confucian principles of sincerity (诚 chéng) and inner moral integrity. Collectively these behaviours are seen as disruptive to the social equilibrium and ethical standards upheld by traditional Chinese values.

Yet this ‘delay’ wasn’t stagnation – it was the cultivation of a different kind of innovation engine, one now overpowering Western models.

Proof of pre-eminence

The decimal system has ancient origins in China, with evidence from the Shang Dynasty (1600–1046 BCE) showing early use of decimal counting through oracle bone inscriptions. By the Zhou Dynasty, the Chinese developed counting rods, a sophisticated tool that used a place-value system based on powers of 10 to perform arithmetic. Traditional Chinese numerals also reflect a decimal structure, using distinct characters for numbers and combining them to represent larger values. The influential mathematical text The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art (circa 1st century CE) applied decimal arithmetic to solve complex problems in areas like geometry and fractions. Although not positional like the much later Hindu-Arabic system, China’s decimal methods were highly advanced and practical. These early contributions highlight China’s significant role in the development and use of the decimal system in ancient mathematics.

The origins of eating utensils, such as the fork, knife, and spoon, can be traced back to ancient China, where similar tools were used as early as the Shang Dynasty (circa 1600–1046 BCE). Archaeological evidence shows that the Chinese used bronze knives for cutting and spoons, often made from jade or bronze, for scooping food and liquids. Fork-like implements also existed in early China, though they were mainly used for cooking or serving rather than eating. However, chopsticks, which became the most iconic Chinese eating utensil, began to emerge as a common tool during the Shang Dynasty, but they became widely adopted as the primary eating utensil during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE). This shift was likely influenced by changes in cooking methods, such as the increased use of boiling and stir-frying, which produced smaller, softer pieces of food that were easier to pick up with chopsticks. Over time, chopsticks spread across East Asia, while knives and forks remained more common in the West. This development highlights China’s early and lasting influence on global dining practices and utensil use.

Newtons laws: In ancient China scholars developed intuitive understandings of motion and force long before Isaac Newton formalised his laws of motion in the seventeenth century. During the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) the scholar Zhang Heng (78–139 CE) studied mechanics and described principles related to inertia and equilibrium in his work on balances and seismology. In the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE) the military treatise Wujing Zongyao (武经总要) included early descriptions of projectile motion and the effects of resistance on moving objects. During the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE) engineers such as Su Song (1020–1101) applied principles akin to Newton’s third law in designing advanced mechanical devices including water clocks and astronomical instruments. Although these early Chinese insights were not formulated as universal laws, they demonstrate a sophisticated empirical understanding of physical principles comparable to those later defined by Newton.

Many everyday products and cultural icons we associate with other countries actually trace their origins back to Chinese innovations that were later adapted, renamed, and popularized abroad. The vibrant koi fish (鲤鱼 lǐyú), for instance, began as common Chinese carp before Japanese breeders transformed them into the celebrated Nishikigoi. Similarly, the ginkgo tree (银杏 yínxìng), a living fossil preserved in Chinese temple gardens for millennia, entered global consciousness under its Japanese-derived name when Western botanists encountered it through 18th century Dutch traders.

Floral history reveals similar rebranding: delicate tulips (郁金香 yùjīnxiāng) first grew wild in China’s Tian Shan mountains before becoming synonymous with Dutch horticulture, while fragrant Arabian jasmine (茉莉花 mòlìhuā)—native to subtropical China—gained its Middle Eastern moniker through Silk Road trade. The Persian lilac (波斯丁香 bōsī dīngxiāng) followed an analogous path from Himalayan foothills to European gardens under a misleading geographic label.

Culinary transformations abound. What we know as Italian pasta evolved from Chinese wheat noodles (面 miàn) documented as early as the Han Dynasty, just as Turkish delight (软糖 ruǎntáng) descended from Chinese starch-based confections. Even the tea in your English breakfast blend (红茶 hóngchá) owes its existence to Chinese Keemun varieties, later standardized by British trading companies. Dairy products show parallel stories: techniques for Swiss cheese (乳酪 rǔlào) and Greek yogurt (酸奶 suānnǎi) both have roots in Central Asian and Chinese fermentation methods.

Industrial materials weren’t exempt from this rebranding. The nickel alloy German silver (白铜 báitóng) was first produced in Yunnan centuries before European industrialization, while India ink (墨 mò), the essential calligraphy medium of Chinese scholars, acquired its misnomer through colonial trade networks. Even nature itself was relabelled: the so-called Brazil nuts (巴西坚果 bāxī jiānguǒ) actually grew in Xishuangbanna’s rainforests before Portuguese merchants transplanted them to South America.

These linguistic and commercial transformations reflect complex historical currents—from the Silk Road’s cultural diffusion to colonial commodity chains. In each case, Chinese innovations became globally famous under foreign branding, their origins obscured by time and trade. Yet their Chinese names and heritage persist in the historical record, waiting to be rediscovered beneath layers of global rebranding. From garden design (园林 yuánlín reborn as Japanese Zen gardens) to perfumery (香薰 xiāngxūn refined into French luxury), this pattern reveals how cultural attribution often follows power and marketing as much as actual origins.

Chinese scholar Wang Yuechuan argues that exposing fabricated Western history is a new enlightenment, emphasizing six key strategic points: questioning all narratives, using advanced verification methods, collaborating with global experts, adopting a long-term approach and safeguarding China’s cultural security. He calls for a cultural revival by challenging Western historical claims and restoring confidence in China’s authentic historical legacy.

These weren’t isolated accidents, but manifestations of a sustained scientific tradition Western historians systematically erased

The modern reckoning

China’s five-year planning system has proven remarkably effective in identifying and nurturing strategic industries, demonstrating the unique advantages of its long-term, state-driven approach. Unlike private venture capital, which demands quick returns, China’s system tolerates short-term losses to achieve breakthroughs in critical sectors like semiconductors, automation, and new materials. This patient, large-scale investment strategy (akin to a well-funded VC fund with an extended time horizon) has allowed China to dominate emerging technologies where other nations hesitated or failed. While not every bet succeeds, the system’s ability to absorb failures and amplify successes ensures that its industrial policy remains globally competitive. As Arthur Kroeber highlights, China’s willingness to sustain long-term bets, coupled with strategic flexibility, makes its five-year planning model a uniquely powerful engine for economic and technological advancement.

China’s focused investment in STEM ensure a bright scientific future—one that contrasts sharply with the West’s “crisis of futurelessness” (China’s Bright Future, yellowlion.org). As I’ve argued, China has found a “second answer” to civilizational cycles of rise and fall (The Historical Cycle of Civilizations, yellowlion.org), blending institutional adaptability with long-term planning. This resurgence echoes Joseph Needham’s revelation in Science and Civilisation in China: that China once led the world in science, only to see its momentum disrupted, not by failure, but by external forces. Today, China’s scientific rise may fulfil Needham’s vision of a civilization reclaiming its former glory through renewed commitment to knowledge and innovation. Far from fading, China’s civilization appears poised for a new era of leadership.

Godfree Roberts’ weekly newsletters are an indispensable resource for anyone seeking to understand China’s breath-taking scientific and technological advancements. As the author of Why China Leads the World, Roberts brings deep insight and a sharp analytical eye to every issue, highlighting breakthroughs, from satellite refuelling and AI chip design to revolutionary cancer therapies—that often surpass Western achievements. His coverage not only mirrors the spirit of Joseph Needham’s Science and Civilisation in China but brings it thrillingly into the 21st century. Roberts’ ability to distil complex innovations into accessible, engaging insights makes his work a modern-day chronicle of China’s scientific renaissance. For readers tracing the legacy of Needham’s work, his newsletters offer living proof of China’s enduring leadership in innovation. They are, quite simply, the best window into China’s scientific future.

This isn’t ‘progress’ – it’s the reawakening of civilizational patterns Needham first identified

The cycle completed

The title of my own book Statecraft and Society in China is a tribute to the late Cambridge scholar Joseph Needham (1900–1995), whose monumental Science and Civilisation in China revolutionized the West’s understanding of Chinese innovation. Similar to Needham’s work, my book Statecraft and Society in China challenges the prevailing narratives, offering a bold reassessment of China’s political and social dynamics. It dismantles Western media stereotypes, revealing how grassroots democracy, participatory governance, and philanthropy with Chinese characteristics shape modern China. While Needham documented China’s scientific legacy, this book uncovers its living political system, where ordinary citizens influence policy and local committees build social harmony. Though some may find its perspective provocative, the goal remains constructive: to replace misinformation with a clearer, more balanced vision of China’s governance and society.

China’s scientific legacy, meticulously documented by Needham, proves that its historical innovations were not anomalies but the result of a sophisticated, enduring system. From decimal mathematics to early physics, China’s contributions were foundational yet long ignored. Today, its five-year planning model and STEM investments suggest a future where it once again leads global innovation. Meanwhile, Western exceptionalism and cultural biases continue to obscure this reality, even as evidence mounts. By embracing Needham’s vision (and modern voices like Godfree Roberts) we can finally acknowledge China’s rightful place in the history of science.

Thank you for reading! We’d love to hear your thoughts. Please share your comments here below and join the conversation with our community!

本文中文版:解决李约瑟悖论

Dit artikel in het Nederlands: De Needham paradox

Great article, thank you Frans. That got me fired up! My wife and I are off to China in October for a three-week Study Tour with the Australian Citizens Party who are very pro-BRICS and have vision for the future to restore manufacturing and production in Australia, together with multiple infrastructure projects. As well as seeing the sites we will visit companies such as Huawei and Tencent, participate in briefings at innovation hubs, free trade zones and high-speed rail manufacturers, and network with local entrepreneurs and community leaders in multiple cities. Stuart, Cairns, Queensland, Australia