Europe’s STEM crisis, a deliberate political sabotage, not an accident.

Views: 112

While we graduate activists, China builds EVs

Frans Vandenbosch 方腾波 21.04.2025

Europe sleeps through the economic crisis.

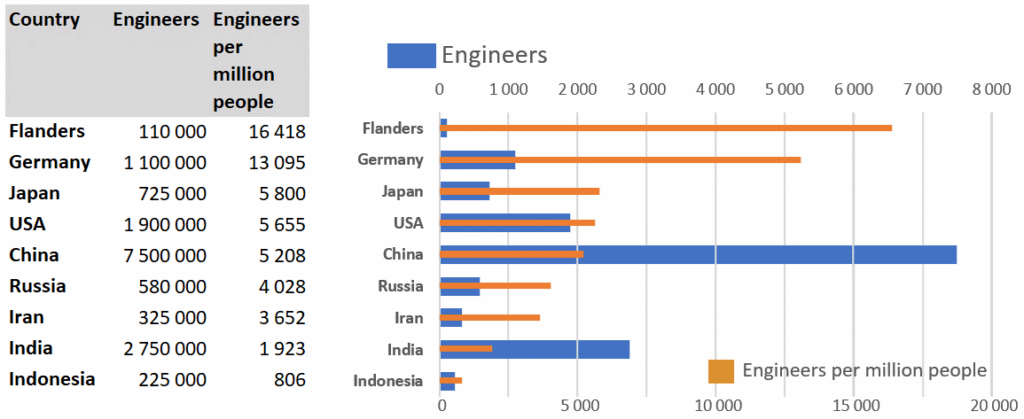

Europe, like the United States, is confronting a severe shortage of highly skilled STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) graduates, particularly in the semiconductor and automotive sector. This issue aligns with the findings of Kevin Walmsley’s extensively researched report (08/04/2025), titled “The US Plan to Build Semiconductors Has a Manpower Problem: China and the BRICS Have All the engineers”

Walmsley’s study, supported by comprehensive data, detailed graphs, and key statistics, demonstrates how the U.S. faces a critical labour shortfall in semiconductor production, while China and other BRICS nations command an overwhelming share of global engineering talent.

However, Europe’s challenges may prove even more daunting. With an ageing workforce, diminishing interest in engineering among students, and intensifying competition from Asia, the continent risks falling behind in the semiconductor industry. Readers seeking a thorough analysis of this global talent disparity are encouraged to consult Walmsley’s insightful report, which provides essential context for understanding Europe’s parallel predicament.

With an ageing workforce, declining engineering enrolment, and Asian competitors outpacing innovation, the continent risks obsolescence in an industry it once led. Walmsley’s data offers not just comparison but warning: without intervention, Europe’s decline will be structural, not cyclical.

Europe’s war on STEM is a war on its own future

Do we, the Europeans, fully realize how dangerous and aggressive it is to promote sociology courses at our universities at the expense of STEM courses? Do we understand sufficiently how far-reaching the consequences of this are?

– Sociologists, here in the West, are trained not to analyse in the first place, but to believe “reliable” sources and reject “unreliable” research studies. This is a very dangerous attitude, which opens the door to easy political manipulation.

– Too many sociologists seems to have forgot that they’re in the tertiary sector, in the service industry. The have completely neglecting their serving role. Some of them even feel they now have to guide the STEM scientists and engineers.

– The sharp decline in the quality and depth of both STEM and sociology studies over the last two decades has brought the Flynn index into negative territory. The IQ level of graduates from our universities has dropped sharply in recent times.

– All this has a devastating effect on both our political system and our economy. Our high-tech companies are forced to move to China, with disastrous consequences for our prosperity and trade balance.

The crisis of western education: How the shift from STEM to sociology is fuelling economic and intellectual decline

A silent but devastating transformation is taking place in Western education systems. While nations like China, India, and other BRICS countries are aggressively expanding their STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) capabilities, Europe and the United States are witnessing a dangerous shift toward sociology and humanities at the expense of technical education. [1][1] This trend carries severe consequences for economic competitiveness, technological sovereignty, and even the intellectual rigor of future generations.

The great STEM decline

Recent data reveals an alarming pattern in Western education. Between 2015 and 2025, engineering enrolments across the European Union declined by 8 percent, while sociology and humanities programs grew by 15 percent. [2][2] The United States faces an even more dire situation, with projections indicating a shortage of 1.4 million tech workers by 2027. [3][3] These numbers stand in stark contrast to China’s educational output. While Western nations struggle to maintain their technical talent pipelines, China now graduates over 600,000 engineers annually, more than triple the combined output of the U.S. and EU. [4][4]

The economic repercussions are already visible. The EU’s high-tech trade deficit with China has tripled since 2020, according to Eurostat. [5][5] Major technology firms including ASML, Intel and Siemens have begun relocating critical research and development operations to China, not merely for cost savings but because they cannot find sufficient numbers of qualified engineers in Western nations. [6][6] This talent drain threatens to erode Western leadership in semiconductors, artificial intelligence, and advanced manufacturing.

The intellectual consequences of sociology’s dominance

Beyond the economic implications, the Western education system’s shift toward sociology and away from STEM carries profound intellectual consequences. Research published in Behavioural and Brain Sciences demonstrates that social science fields exhibit extreme ideological homogeneity, actively discouraging dissenting viewpoints. [7][7] A 2023 study in PNAS found that sociology journals reject papers contradicting dominant narratives at three times the rate of STEM publications. [8][8]

This intellectual conformity appears to be producing measurable declines in critical thinking. Data from the OECD’s PISA assessments show consistent drops in logical reasoning and problem-solving skills among Western students. [9][9] Perhaps most alarmingly, the Flynn effect, which documented rising IQ scores throughout the 20th century, has reversed in Western nations. Intelligence research now shows declining cognitive performance, particularly in mathematical and scientific reasoning. [10][10]

The economic and geopolitical fallout

The consequences of this educational shift extend far beyond university campuses. In the semiconductor industry alone, Europe faces a projected shortfall of 15,000 engineers by 2030 despite needing 100,000 additional skilled workers. [11][11] The workforce crisis is compounded by demographic challenges, with only 18 percent of European engineers under age 30 compared to 44 % in China. [12][12]

This talent gap has forced Western firms to make difficult choices. Intel relocated chip design operations to Shanghai after failing to hire 500 engineers in Western nations. [13][13] ASML moved AI research to Shenzhen due to talent shortages in the Netherlands. [14][14] These decisions create a vicious cycle, as the relocation of high-tech jobs further diminishes opportunities for Western STEM graduates, accelerating the brain drain to Asia.

A path forward

Reversing this decline will require concerted action across multiple fronts:

- Revitalizing STEM education through targeted scholarships, curriculum reforms, and early exposure programs to reignite student interest in technical fields.

- Retaining top talent by offering competitive salaries, research funding, and immigration policies that keep foreign STEM graduates in Western countries.

- Aligning academic programs with industry needs to ensure graduates possess skills relevant to critical sectors like semiconductors and artificial intelligence.

Without immediate intervention, the West risks permanent technological dependence on China and other BRICS nations. The time for action is now, before the growing gap in technical capabilities becomes irreversible.

Europe’s glorious post-industrial utopia: Deconstructing ourselves into irrelevance

If we truly want to rebalance our trade deficit and revive manufacturing, the solution is obvious: We’ll put our army of lawyers, social workers, and gender studies graduates to work on the assembly lines—not for complex tasks, mind you (we wouldn’t want to overwhelm their skill sets), but for the gloriously simple, repetitive labour that once belonged to machines and trained technicians.

Imagine the efficiency! A theologian carefully soldering circuit boards, pausing only to ponder the existential implications of each connection. Picture a team of sociologists performing quality control, rejecting defective parts not because they fail technical specifications, but because they reinforce oppressive power structures. And who better to oversee production than a pedagogue, ensuring every screw is tightened in accordance with the latest inclusive, non-hierarchical workplace guidelines?

Meanwhile, our engineers—those few still left—will watch in awe as critical theorists debate whether the factory itself is a colonialist construct, while China quietly annexes the last remaining sectors of advanced manufacturing. But fear not! Once Europe’s industrial base has been fully dismantled, we’ll have all the time in the world to write beautifully nuanced essays about our decline. After all, if we can’t compete in the global economy, at least we can critique it with unparalleled sophistication.

If Europe insists on staffing its factories with sociologists while outsourcing engineering to Shenzhen, we shouldn’t act surprised when our “industrial strategy” is reduced to writing grant proposals about post-growth utopias—printed on Chinese-made paper, of course.

The irony is almost too perfect: A continent that once mastered precision machinery now excels mainly in producing non-judgmental mission statements about why none of this is our fault. “The robots took our jobs? No—we deconstructed the very notion of ‘jobs’ as a capitalist construct!” Meanwhile, Beijing laughs all the way to the patent office.

But worry not—when the last German engineer retires and the final French lab switches to decolonizing quantum physics, we’ll still have one world-class export left: Sarcasm. And unlike semiconductors, it doesn’t require a skilled workforce.

…

Endnotes

[1] OECD, STEM vs. Humanities Enrolment Trends (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2025).

[2] Eurostat, Education Statistics (Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2025).

[3] European Commission, Digital Skills Gap Report (Brussels: EC Publishing, 2025).

[4] OECD, Global Education Outlook (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2025).

[5] Eurostat, High-Tech Trade Deficits (Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2025).

[6] “Tech Giants Move R&D to Asia,” Financial Times, May 12, 2025.

[7] José Duarte et al., “Political Bias in Social Science,” Behavioural and Brain Sciences 38 (2015): 1-15.

[8] “Peer Review Bias in Sociology,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 120, no. 15 (2023).

[9] OECD, PISA 2024 Results (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2024).

[10] Edward Dutton, “The Negative Flynn Effect,” Intelligence 56 (2016): 112-119.

[11] Semiconductor Industry Association, Global Talent Report (Washington, DC: SIA, 2023).

[12] “Europe’s Aging Engineering Workforce,” Bloomberg, January 10, 2025.

[13] “Intel’s China Expansion,” Financial Times, June 15, 2024.

[14] “ASML’s Asian Research Shift,” Bloomberg, March 22, 2025.

Thank you for reading! We’d love to hear your thoughts. Please share your comments here below and join the conversation with our community!

本文英文: 欧洲的 STEM 危机,是一场蓄意的政治破坏,而非意外。

Dit artikel in het Nederlands: Europa’s STEM-crisis, een opzettelijke politieke sabotage, geen ongeluk.

Like the USA, the EU will become a rules taker, not a rules maker, by the end of this year.

Extremely rigorous article full of relevant data, very informative and endowed with a pristine interpretation : your usual trademark, Frans !

In case you don’t know the name of Charlotte Thomson Yserbit (1930-2022), I suggest you give a glance at her book called : The deliberate Dumbing Down of America : A Chronological Paper Trail (published in 1999)

She published in 1985 *Back to Basic Reforms*

The 2 books can be easily obtained in pdf format.

According to Yserbit, the systematic dumbing down of the US Education System originated from plans formulated primarily by the Andrew Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Education and the Rockefeller General Education Board.

Since the European Nations have been utterly vassalized by the US, I think it’s NOT an unhinged conspiracy theory to suggest that the plan used for the US has also been somehow implemented in Europe through the usual alphabet soup agencies but I think that you definitely don’t need my help for formulating that glaring hypothesis.

Quan Li

Hello Quan Li

Thank you for the book tip.

Only this morning, someone wrote me: “You’re right, they’re indeed educate too much sociologists and other people who’re easy to manipulate. STEM education is suppressed. But I can’t believe it is a deliberate plan”