Views: 59

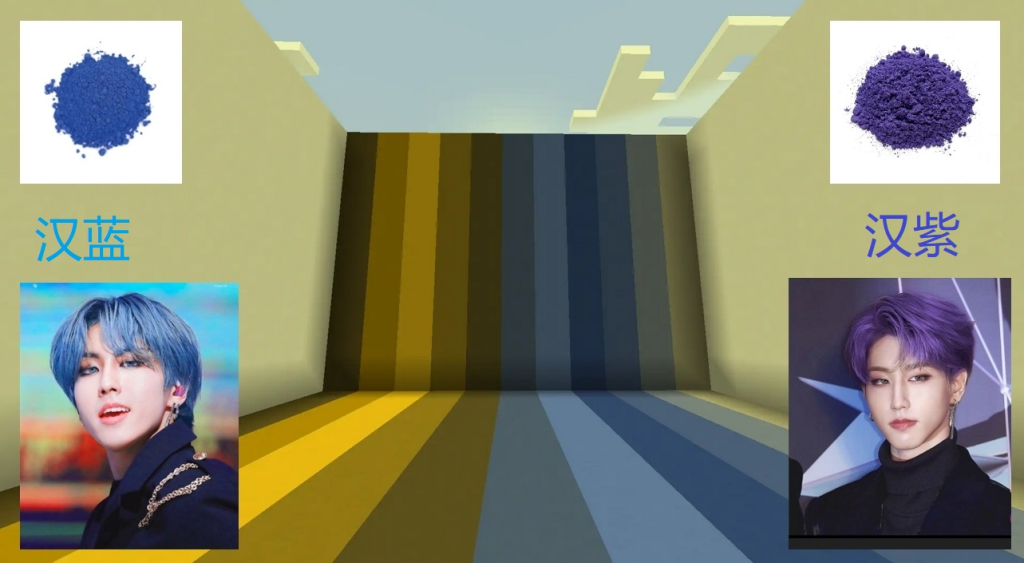

The super-conductivity of Han-blue.

Frans Vandenbosch 方腾波 19/01/2026

The alchemists who conquered colour: how ancient China mastered synthetic chemistry 2,800 years before Europe.

Long before European chemists stumbled upon synthetic dyes in their 19th-century laboratories, Chinese artisans were already masters of an extraordinarily sophisticated science. Almost three millennia ago, during the Western Zhou dynasty (around 1046–476 BC), they achieved what modern physicists can barely replicate: the deliberate creation of compounds that have never existed naturally on Earth.

This wasn’t accident. This was precision chemistry executed with such mastery that it would take humanity another 2,800 years to match it.

Han Purple and Han Blue stand as monuments to this ancient genius. These barium copper silicate pigments (BaCuSi₂O₆ and BaCuSi₄O₁₀) required a level of chemical precision that defies belief. Consider what these artisans accomplished without modern instruments, without thermometers accurate enough to measure kiln temperatures, without any conception of atoms or molecular structures. They worked purely through empirical observation; metallurgical knowledge accumulated over generations and extraordinary patience.

The manufacturing process itself reads like advanced materials science. Artisans had to source exact minerals: witherite or baryte for barium, specific copper compounds, pure quartz for silica and lead salts. Each ingredient had to be weighed and ground to precise consistency. The mixture then entered kilns where it faced the ultimate test: sustained temperatures between 900°C and 1100°C for ten to 48 hours. A few degrees too cool and the reaction wouldn’t complete. Too hot and the entire batch would be ruined.

The lead component deserves particular attention. Its use as a flux and catalyst represents a distinctively Chinese innovation, absent from similar Egyptian pigments. This wasn’t merely adding another ingredient; it demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of how certain materials could facilitate chemical reactions. Modern chemists recognise this as genuine catalytic chemistry, a concept supposedly not formalised until the 19th century.

The results were breathtaking. Analysis of the Terracotta Warriors (circa 210 BC) reveals purple reaching over 95 per cent purity! That 95 per cent purity was achieved in kilns fired with charcoal, controlled by eye and experience alone. Contemporary pharmaceutical-grade chemicals would be proud of such specifications.

For 1,200 years, from the Spring and Autumn period through to the Han dynasty’s end in 220 AD, these colours adorned ceremonial objects, lacquerware and imperial art. The pigments became symbols of sophistication and technological prowess, used on objects destined for emperors and the afterlife alike. When Qin Shi Huang was laid to rest with his terracotta army, these synthetic purples and blues were deemed worthy to accompany China’s first emperor into eternity.

Then, mysteriously, the knowledge vanished. The techniques died with the decline of Taoist alchemy and early glassmaking traditions that had birthed them. For over a millennium, humanity forgot how to create these colours. The loss represents one of history’s great technological discontinuities, comparable to the loss of Roman concrete or Greek fire.

A palette beyond compare.

Han Purple and Han Blue were merely the crown jewels in China’s colour empire. The civilisation commanded an extraordinary palette that would envy any modern colourist.

Red dominated Chinese colour symbolism with multiple sources. Madder root provided foundational textile reds through careful mordanting for colour fastness. Cinnabar and vermilion (from mercury sulphide minerals) gave painters brilliant scarlets. The lac insect yielded deep crimsons. Safflower, arriving via the Silk Road from Central and Western Asia, produced the purest reds imaginable. Sappanwood enriched the spectrum further. This wasn’t merely having options but mastery over every shade from pink through crimson to deep burgundy.

Yellow held special significance, reserved by law for imperial use in its most brilliant forms. Gardenia provided reliable yellows for common use, whilst berberine plants (particularly cork tree bark and barberry) offered manipulable yellow tones. Pagoda tree buds gave seasonal yellows. Chinese artisans even employed toxic mineral yellows like realgar and orpiment in painting, valuing colour so highly they’d work with dangerous materials.

Blue belonged to indigo completely. Multiple indigo species grew across China’s diverse climates. The fermentation vat process represents chemistry’s most elegant tricks: the water-insoluble dye compound required an alkaline fermentation environment for temporary solubility. Textiles soaked in this greenish-yellow liquid oxidised in air, the blue appearing magically. This process, perfected over millennia, produced deeply colourfast blues synonymous with Chinese textiles. Azurite (a copper carbonate mineral) provided painters with brilliant blues.

Purple posed challenges everywhere, but China answered with gromwell root (a plant-based dye requiring expertise) and synthetic Han Purple. Pursuing both natural and artificial routes demonstrated their comprehensive approach to technical problems.

Green came primarily from malachite, another copper carbonate mineral. Black resulted from tannin-rich plants (particularly oak galls) combined with iron mordants, creating intense, permanent dye. Alternatively, fabrics could be overdyed repeatedly with indigo.

The crucible of exchange

China didn’t develop this mastery in isolation. The Silk Road transformed Chinese colour technology from regional achievement into global phenomenon whilst enriching China’s capabilities.

Chinese silk became the most coveted luxury commodity across three continents because of its colour. Silk dyed with Chinese indigo possessed depth and lustre impossible with wool or linen. Madder-dyed silks commanded extraordinary prices in Roman markets as proof of China’s technological superiority.

Trade wasn’t one-directional. Safflower from Central Asia produced clear, bright reds. Sappanwood from Western Asia added another option. These introductions enhanced Chinese achievement. The Chinese demonstrated sophistication through selective adoption and improvement of foreign techniques.

Chinese dyers didn’t copy imported methods. They adapted them, combined them with existing knowledge and often surpassed the original. When turmeric arrived from South Asia, dyers found optimal applications. This pattern would characterise Chinese technological development for millennia.

Colour and empire.

In ancient China, colour carried power. This wasn’t metaphorical; it was law. The imperial yellow, derived from specific sources and produced through guarded techniques, could only be worn by the emperor and his immediate family. Violation meant death. This restriction wasn’t arbitrary vanity; it was a visible manifestation of cosmic order. The emperor’s yellow connected him to the earth and centre, the fundamental source of imperial authority.

Similar restrictions governed other colours at various periods. Purple, that colour so difficult to produce anywhere in the ancient world, naturally became associated with nobility and high officials. The possession of Han Purple items signalled not merely wealth but connection to imperial workshops and state resources.

The symbolism extended beyond status. Red represented joy, celebration and good fortune, making it essential for festivals and weddings. Black and white carried funerary connotations but also represented water and metal in the five-element system that structured Chinese cosmology. Blue connected to wood and spring, green to growth and harmony. Colours weren’t decorative choices; they were meaningful statements embedded in a sophisticated symbolic language.

The 17th-century encyclopaedia Tiangong Kaiwu devoted substantial sections to dye production, documenting techniques for creating dozens of colours from local plants. Written by Song Yingxing during the Ming dynasty, this text preserved knowledge stretching back millennia. The level of detail astounds: precise fermentation times for indigo vats, mordant combinations for different effects, seasonal variations in plant material quality. This was chemistry recorded as practical instruction, waiting for future scientists to recognise it as such.

The long silence.

After the Han dynasty collapsed in 220 AD, something precious was lost. The techniques for creating Han Purple and Han Blue vanished, taking with them over a millennium of accumulated knowledge. Scholars have proposed various explanations: the decline of Taoist alchemical practices, the disruption of trade routes that supplied rare minerals, the loss of specific kiln technologies as metallurgical practices evolved. Perhaps all these factors combined. Whatever the cause, by the Tang dynasty (618–907 AD), no one remembered how to make these colours.

The pigments themselves survived on ancient objects, fading slowly over centuries. Painted warriors stood guard in sealed tombs. Lacquerware boxes mouldered in burial chambers. Han Purple persisted in these dark places, waiting.

For a thousand years, the secret slept.

Resurrection through science.

The modern rediscovery of Han Purple reads like archaeology’s greatest detective story. When Chinese archaeologists began excavating the Tomb of Qin Shi Huang in 1974, they found an army unlike anything in history: over 8,000 life-sized terracotta warriors standing in battle formation. The sculptures themselves commanded attention, but some archaeologists noticed something else: traces of vivid paint.

Most had flaked away over 2,200 years, but fragments remained. Among them were purples and blues of such intensity they seemed impossible for ancient pigments. Natural purple dyes (like Tyrian purple from molluscs) fade to brown or grey over centuries. These hadn’t. That persistence demanded explanation.

Samples went to laboratories equipped with X-ray fluorescence and diffraction spectrometry, tools that could identify materials at the atomic level without destroying precious artefacts. The results stunned researchers. This wasn’t any known natural mineral. The barium-copper-silicate composition matched nothing found in nature. Someone, somehow, had made these colours from scratch.

This realisation transformed understanding. If the ancient Chinese had created synthetic pigments requiring high-temperature chemistry, what else had they achieved? Teams from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Stanford University launched projects to reverse-engineer the ancient recipes. They experimented with mineral combinations, kiln temperatures and firing times. Slowly, through systematic experimentation, they confirmed the extraordinary sophistication required: precise mineral ratios, sustained temperatures above 900°C and that crucial lead flux acting as catalyst.

Modern chemistry could barely improve on the ancient results. When contemporary scientists recreated Han Purple using controlled electric kilns and pure reagents, their product achieved similar purity to samples from the Terracotta Warriors. The ancient artisans, working with charcoal-fired kilns and ore-derived minerals, had matched modern laboratory standards.

The quantum surprise.

The most astonishing discovery about Han Purple came from an unexpected direction: quantum physics. In the early 2000s, physicists examining magnetic materials became curious about this ancient pigment. They cooled samples to near absolute zero (minus 273°C) and subjected them to powerful magnetic fields.

What they observed defied expectations. At extreme cold, the copper atoms in Han Purple’s crystal structure arranged themselves in chains. The electrons in these chains behaved in highly unusual patterns, exhibiting what physicists call “one-dimensional quantum behaviour.” This phenomenon appears in cutting-edge materials being developed for quantum computers and high-temperature superconductors.

Think about what this means. Ancient Chinese alchemists, searching for methods to create jade-like colours, synthesised a material exhibiting quantum mechanical properties that modern physicists struggle to produce intentionally. They created a substance that would, 2,000 years later, interest researchers at the absolute frontier of physics.

Han Purple bridges ancient art and modern quantum mechanics in ways no one imagined possible. Papers in physics journals now cite archaeological research. Quantum physicists reference the Terracotta Warriors. This isn’t merely historical curiosity; it’s active scientific investigation of a material whose properties remain incompletely understood.

The first colour revolution

When history textbooks discuss the synthetic colour revolution, they typically begin in 1856 when William Henry Perkin accidentally created mauveine whilst attempting to synthesise quinine. This “first” synthetic organic dye launched the modern chemical industry and transformed global economics. That story is true and important.

But it’s incomplete.

The first colour revolution occurred in China’s kilns during the Western Zhou dynasty, around 1046–476 BC. Comparisons with other ancient civilisations illuminate China’s achievement. Egyptian Blue, made from calcium, copper and silicate, was humanity’s first known synthetic pigment. Widely traded across the Roman Empire, it adorned temples and palaces from Britain to Mesopotamia. Yet for all its success, Egyptian Blue never achieved the brilliance of Han Purple. The Egyptians never mastered the use of lead flux as a catalyst, a crucial innovation that allowed Chinese artisans to achieve far superior purity and intensity. The Egyptians deserved their reputation for colour mastery, but Chinese chemistry surpassed it.

Maya Blue (circa 800 AD) demonstrated Mesoamerican sophistication. This organo-clay hybrid combined indigo dye with palygorskite clay in a way that created extraordinary weather resistance. Murals painted with Maya Blue survive exposed to elements that destroy other pigments.

Yet Han Purple stands apart. Its quantum properties make it unique even amongst these technological marvels. While Egyptian Blue and Maya Blue were magnificent achievements, neither exhibits the exotic physics lurking in Han Purple’s crystal structure.

Legacy and triumph.

What does this history reveal about ancient China? It demonstrates a civilisation at the pinnacle of pre-modern technology. Chinese artisans were practical scientists conducting systematic experiments and refining techniques across generations.

Creating Han Purple required staggering sophistication. Without thermometers, artisans recognised optimal kiln conditions through flame colour. Without understanding atomic structure, they determined mineral ratios through methodical testing. Without chemical theory, they recognised lead’s catalytic role through pure observation.

This represents science in its truest form: careful observation, systematic experimentation and accumulated knowledge. China’s colour mastery extended far beyond one pigment, creating a complete system of sophisticated dyeing techniques and complex chemistry.

The Silk Road demonstrates China’s confident engagement with the world. Chinese merchants exported dazzling dyed goods whilst selectively adopting and improving foreign techniques.

China blue.

Han blue (汉蓝) and porcelain china blue (青花瓷) are distinct. Han blue (barium copper silicate) was a synthetic pigment used for artefacts like terracotta warriors until the Han dynasty. The blue for porcelain (cobalt-based) was used from the Tang dynasty onwards for decorating ceramics. They are different chemically and historically with no technical lineage. Both represent significant achievements in Chinese artistic technology but are from separate eras.

How Chinese porcelain blue came to Europe, and later was copied in Delft, that’s material for a next article.

Thank you for reading! We would love to hear what you think. Share your comments below and join the conversation with our community!

本文中文版:

Dit artikel in het Nederlands: Een antieke kleurenrevolutie.