Views: 337

Has China’s excessive automation and robotisation caused overcapacity ?

Frans Vandenbosch 方腾波 28.04.2024

Back in 2015…

Back in 2015, living in Suzhou, working in Wuxi, I noticed an overwhelming wave of investments in automation and robotisation. In the automotive industry, automation was already very common. But in small manufacturing enterprises, there were assembly lines with dozens of mostly female workers. These were the young sons and daughters, born in Western China who moved to the more developed cities at the East coast of China.

At that time, salaries were moderate, and the quality of the products was not top level. Competition was based on price, not on quality.

But then, almost all of a sudden, I noticed an explosive growth of Chinese automation companies. These companies were designing automation, integrating sensors, quality monitoring camera’s and robots in the assembly lines up to complete assembly lines without the need for operators.

In most cases, the excessive investment in automation was economically and financially unjustifiable. Salaries were going up, but there was not an urgent need to invest in automation to save labour cost.

Then, why were all these small and big Chinese companies so heavily investing in automation ?

It’s the quality, stupid

Manual assembly depends on humans, and humans are fallible and unstable. These Chinese entrepreneurs had understood that if they wanted to take the quality of their products to a higher level and thus compete with products from more industrially developed countries, they had no choice but to invest in automation.

A robot or an automated assembly machine does not make the mistakes that a sometimes absent-minded or inattentive person makes. A robot is making or assembling products in a steady, stable pace. It can be fine tuned step by step until perfection.

At that time, back in 2016, I have seen complete assembly lines from raw materials until the loading in a shipping container. Often, these assembly lines were operating in a production hall entirely in the dark, with no people at all in the entire production facility. Naturally, a quality engineer will inspect the line and the products at regular intervals. And if necessary, an automation engineer will adjust the robots and automation systems.

Disruptive

Very few people, let alone the famous western economists realized how this wave of automation in China was having profound consequences for the economy in the West. When, one year later, the salaries in China were rising significantly, most western economists were convinced that the automatization wave was to save labour costs. It indeed sounds logical. But the truth was much more profound and with far-reaching consequences.

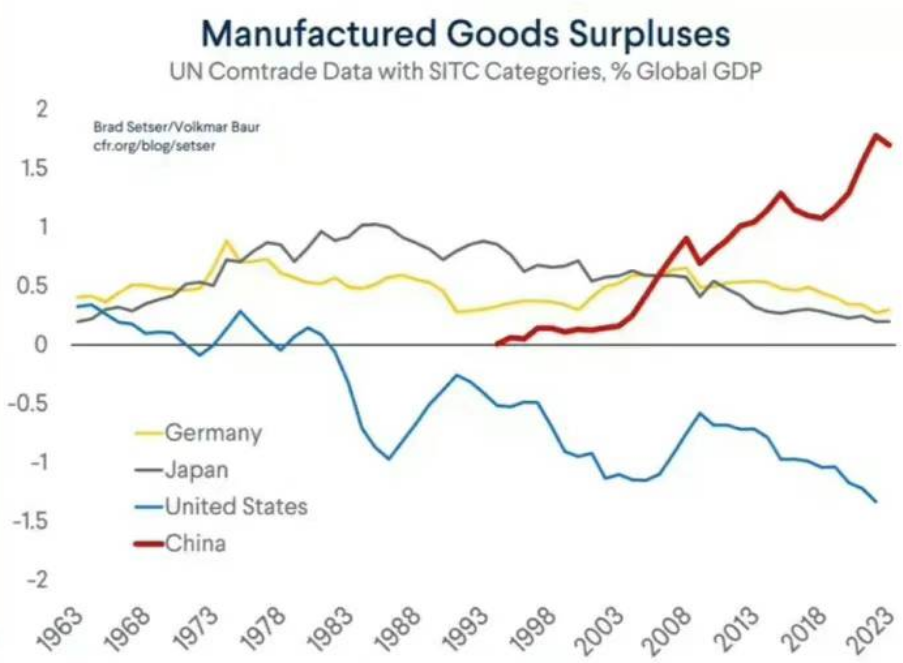

As I have written in several articles and emails at that time: the western economy will be unable to withstand this. The Chinese automation wave will cause a significant improvement in the quality of Chinese products and combined with the very competitive price of Chinese products; this will be a serious blow to the Western economy. Nobody believed me, nobody was ready to understand the consequences. Western industry did not want to know and did not take the necessary measures to improve their global competitiveness. Western governments did not realize that the death sentence of their economy was coming.

Today

Today, with the investments in automation almost written off, we are seeing the astonishing results. China is making top quality products at a very competitive price level, often ¼ or less than the price in western countries.

The automation wave in China continues to this day and will go beyond what we have ever seen in the West. Once the automatic production lines are functioning, it is easy peasy to increase the speed or set up a second copy/paste production line.

China indeed produces all kinds of products, semi-finished products, luxury products, advanced technology, nutraceuticals, excipients, pellets, and other basic raw materials for medicines. They are making these products for the huge Chinese market and for export to countries all over the globe.

Does that mean that there is any overcapacity in China ? Is a surplus capacity, a capacity to produce more than what’s needed for local consumption, an overcapacity ?

The “overcapacity” where Blinken is accusing China from, is a fairy tale, a narrative to blame China for the lack of competitiveness of the American economy.

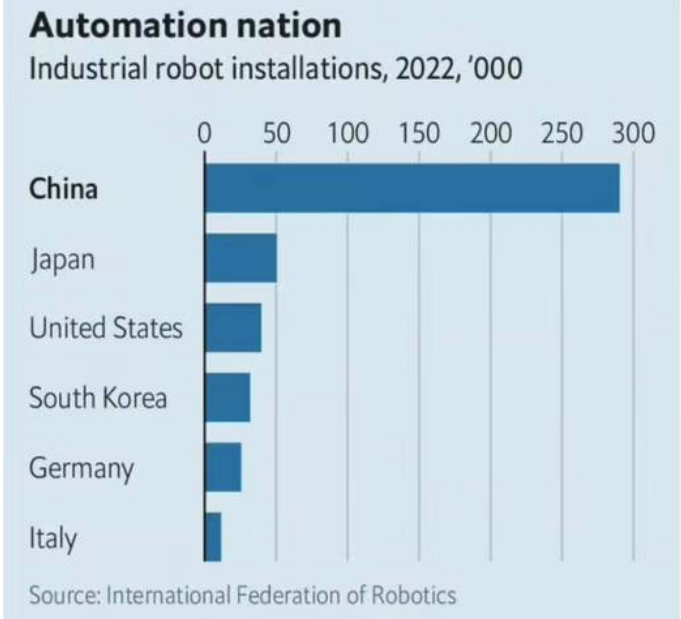

The automation and robotisation wave, started in China in 2015 was even accelerated by the US tariffs from 2018 on. Today in China it is a given that when a new production is set up, it must be fully automated. And we are not at the end yet. In addition to the automation wave, there is now the new AI wave. This is gradually conquering the automatic production lines, so that soon even the quality engineer or automation expert no longer will have to intervene.

Conclusion

In summary, I must conclude that the Chinese entrepreneurs who invested in automation back in 2015 were after all very right. They had the vision and long-term planning. For Western companies, the only choice remains between cooperation with China or total collapse. Western economical experts didn’t noticed this wave; they were – once again – wrong.

This is the shortest, most insightful article I have read on automation in China. Many thanks!

The invisible elephant in this article is the Chinese work force displaced by the wave of automation. Where did it go? Was it absorbed in other sectors of the rising Chinese economy or did it become a serious social problem as it has in the West?

Karl

The automation wave in China has not caused any unemployment. The abundant (mostly young, female) assembly line workers got retraining and managed to get other kinds of employment. Most of them already had one or another specialised education; assembly line workers in China are not per definition uneducated, poor people.

Something similar is currently going on with AI, replacing even higher educated staff in many companies.

The unemployment rate in China is very low.

There’s no elephant in the room.

China would be the place to make large-scale automation work, by considering its employees. After all, no Western country, for instance, could raise up the mass of its poorest people as China has done. But when you say, “The abundant (mostly young, female) assembly line workers got retraining and managed to get other kinds of employment,” could you substantiate this with more information. The statement seems a little sweeping and general.

Simon

I do not have exact figures or statistics here. But as I wrote here above, many of the (mostly female) assembly workers already had higher education. Many of them did simple assembly work because they couldn’t immediately start working in the field for which they received school training. In China I have seen doctors, saleswomen, lawyers, archaeologists and others working on an assembly line.

When I see the current unemployment figures in China, it is clear that today, 10 years after the automation wave, those layoffs have not caused significant unemployment.

Moreover: since 2015, the Chinese government and industry have made significant efforts to manufacture more high-tech products. These new industries have largely absorbed the former line workers.

In China the pie is not divided, but continually made bigger.

Any economy that does not invest in automation and production is doomed to be superseded by the economies that do. Recently a railway mechanic/technician, not an engineer, told me that the Chinese railway company is experimenting with robots doing repairs. The railway repairs one out of ten trains with robots and then has workers overlook and check the robot’s work.

I can’t imagine a Western company daring to divert income from shareholders into experimentation and development. Not that they have much income, with energy prices being artificially high due to the American sanctions on Russia and misguided “green” energy policies.

In the West the concept of “shareholder value” has led to firms eating their own capital to provide high stock prices to shareholders. I think an article about the Chinese understanding of shareholder value would be a good read.