Views: 105

Beijing

Frans Vandenbosch 方腾波 30/09/2025

The barbarians in Beijing

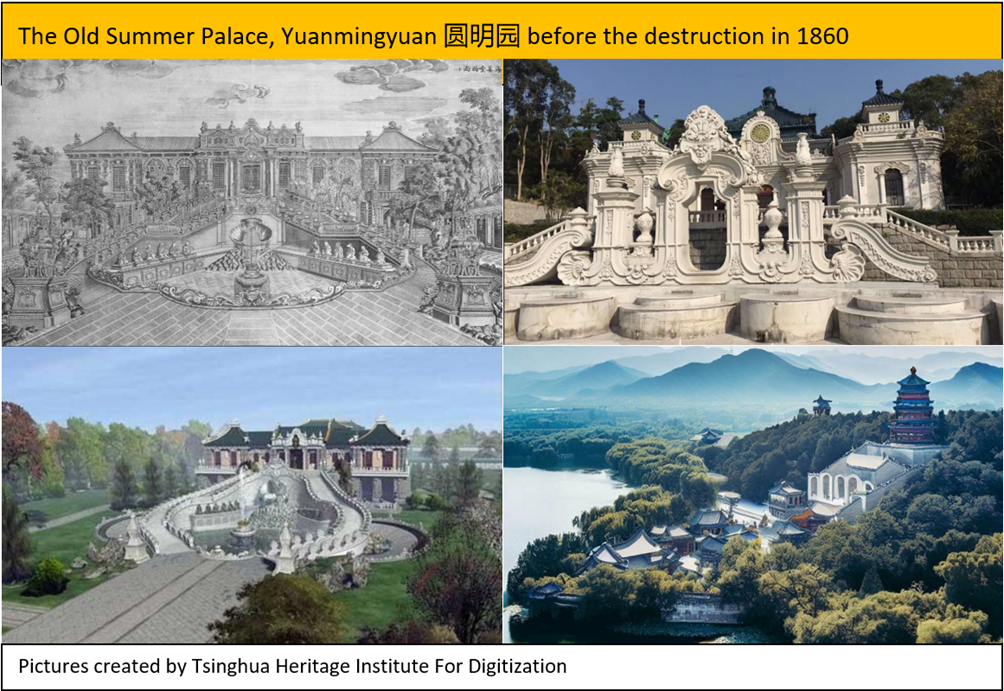

The Old Summer Palace, the Yuanmingyuan “圆明园” in Chinese, located in the Haidian district of Beijing, was a large imperial garden that the emperors of the Qing Dynasty operated for over 150 years. It was known as the “Garden of Gardens.”

The Imperial Gardens were made up of three gardens:

– Garden of Perfect Brightness (圆明园; 圓明園; Yuánmíng Yuán)

– Garden of Eternal Spring (长春园; 長春園; Chángchūn Yuán)

– Garden of Elegant Spring (绮春园; 綺春園; Qǐchūn Yuán)

Together, they covered an area of 3.5 square kilometres, almost five times the size of the Forbidden City and eight times the size of the Vatican City. There were hundreds of structures, such as palaces, halls, pavilions, temples, galleries, gardens, lakes and bridges.

Yuanmingyuan was arguably the greatest concentration of historic treasures in the world, dating and representing a full 5000 years of an ancient civilization.

In 1860, the 10th year of the Xianfeng (咸丰) era, the British and French troops looted and burned Yuanmingyuan down. It was the British High Commissioner to China, James Bruce, the 8th Earl of Elgin, who gave the final order for the destruction of the Yuanmingyuan (Old Summer Palace) in October 1860. The destruction was not a spontaneous act of violence by soldiers but a calculated decision made at the highest level of British command, approved by Elgin as a political and military tactic. The French forces, under Commander-in-Chief Charles Cousin-Montauban, initially opposed the action as being outside the rules of war, though they were active participants in the earlier looting of the palace.

For two days before the burning, the French and British troops engaged in widespread looting. What was taken were smaller, valuable, and portable objects:

- Artworks: Jade carvings, porcelain vases, enamelware, silk tapestries.

- Jewellery: Gold, silver, and precious gemstones.

- Clocks: The palace had a famous collection of elaborate clocks and automata.

- Bronzes: Intricate bronze statues and ritual vessels.

- Books and Scrolls: Ancient manuscripts and paintings.

These smaller, immensely valuable items were easily packed into crates and shipped back to Europe, where many ended up in national museums (like the British Museum or the Musée Guimet in Paris) or in private collections.

Today, the large majority of the looted Yuanmingyuan artifacts remain in Western museums and private collections. There have been no major, successful government-led negotiations for their mass return. The primary method of repatriation has been repurchasing items on the open market, which is a contentious and expensive process. The issue remains a powerful symbol of historical injustice and a point of ongoing diplomatic and ethical debate in the world of museum culture.

After looting and burning the palace complex, the focus shifted to systematically destroying the marble structures in place rather than removing them. The white marble buildings, particularly the European-style palaces designed by Jesuit priests, were seen as powerful symbols of imperial authority that needed to be completely eliminated for maximum psychological impact.

The destruction of the buildings involved two main approaches:

Manual demolition using basic tools and techniques: soldiers employed crowbars and sledgehammers to pry apart and smash marble blocks, used wooden beams as levers with pivot points to topple large statues and columns, and utilized ropes with human or animal power to drag heavy pieces from their foundations so they would shatter upon impact.

Controlled explosions using available military gunpowder. Teams drilled strategic holes in structural weak points like pillar bases and block joints, pack these holes with black powder from their military supplies, then detonate them with fuses. The explosions were designed not to pulverize the marble but to create enough force to fracture, destabilize, or topple the structures, making them easier to finish destroying by hand.

This systematic approach ensured the complete destruction of these symbolic imperial structures on-site, maximizing both the practical elimination of the buildings and their psychological impact as demonstrations of the emperor’s diminished power.

The looting, burning and destruction of Yuanmingyuan went on for several weeks by many dozens of British and French soldiers.

The Haiyan Hall was the largest sight in the Xiyanglou area. It was built in 1759, the 24th year of the reign of Emperor Qianlong. The main building faced the west and had 11 rooms on both floors. On both sides of the front door were two arc-terraced fountains, which led to a large fountain downstairs. Bronze statutes of human bodies with animal heads, representing the 12 symbolic animals associated with the 12 year cycle of human births, were arranged around the large fountain. Each of these animals jetted water for two hours in the sequence of China’s 12 two-hour time dividing system and all the animals jetted water simultaneously at noontime. As a result, it was also called the Water Clock. Behind the Haiyan Hall was an L-shaped building, which supplied water to the nearby fountains.

Three of the bronze beast heads are now in France and Taiwan, while the heads of the ox, tiger, monkey and pig are in the custody of the Baoli Art Museum.

To stand amidst the sprawling desolation of the Yuanmingyuan is to feel the ghost of a murdered masterpiece. Everywhere you look, the earth is littered with the corpse of a dream: shattered columns, fractured friezes, and great blocks of once-gleaming white marble that now lie like fallen giants, scattered in a grotesque mockery of their former glory. This was not merely a palace; it was the largest and most exquisite palace complex our world had ever seen, a zenith of artistic and architectural achievement, a “Garden of Gardens” painstakingly created over centuries. And it was systematically, deliberately, and barbarically erased from existence.

The sheer, wanton violence inflicted upon this place is not just saddening; it is sickening. It is impossible to comprehend the mindset of the men: the French and British soldiers and their commanders, who, in the year 1860, marched through these halls not with awe, but with avarice. They did not simply conquer; they desecrated. They did not merely claim victory; they engaged in an orgy of looting, stuffing their pockets and their ships with countless treasures, and then, in an act of pure, petulant malice, set the impossible-to-steal structures ablaze. To burn what you cannot possess is the ultimate act of a petty and vindictive mind, a betrayal of every principle of civilization they claimed to represent.

This was not just an act of war; it was a premeditated crime against culture itself, orchestrated by nations that boasted of their own enlightenment. France and Britain, who held themselves as beacons of civilization and sophistication, proved themselves to be nothing more than vandals on an epic scale. They did not just destroy a Chinese palace; they assaulted the shared heritage of all humanity, scarring the soul of our world forever. The tears that come to my eyes here are not just of sadness, but of burning, righteous anger. They are tears for the beauty lost, for the history silenced, and for the profound hypocrisy of those who preached civilization while practicing cultural genocide. The ruins of Yuanmingyuan stand today not as a monument to the past, but as an everlasting indictment. They are a permanent, open wound and a damning testimony to the day when European empires, in a fit of jealous rage and imperial arrogance, decided that if they could not possess such beauty, then no one could. The memory of their betrayal is etched into every broken stone, and the emotional weight of their crime is a burden that time has done nothing to lift. It is a heartbreaking, infuriating, and utterly devastating spectacle.

Thank you for reading! We’d love to hear your thoughts. Please share your comments here below and join the conversation with our community!

本文中文版:

Dit artikel in het Nederlands: Azië reis 2025 – deel 3

Britain, France, and the US have always been openly hostile and destructive toward Asia, and China in particular. Their policies and attitudes of Western European, Christian, Capitalistic, manipulated news media superiority toward Latin America, Africa, and Asia do not build global peace and prosperity.

It is disappointing that people in America with much less experience in China claim that their views are better while their government and economy is falling apart with corrupt, incompetent politicians and business leaders, and poorly educated voters and workers.

Thanks Frans for reporting on your travels in China.

Dear Frans, your article represents the conscience of humanity. The remains of the Yuanmingyuan will continue to remind us of the western hypocrocy and treachury toward other people. The French and British will be held in the pole of shame forever.